It's Mother's Day and I've enjoyed handmade cards, a shirt with my kids' pictures on it, and some handmade jewelry. We ate a delicious dinner (I wonder if I can grow fennel in my back yard...I love fennel), complete with a scrumptious chocolate chip cake. I got to take a walk around the lake and read my book. I wasn't upset by Mother's Day talks. I talked to my mom. The only wrinkle: my Mother's Day present to myself hasn't yet arrived from Amazon.

It's Mother's Day and I've enjoyed handmade cards, a shirt with my kids' pictures on it, and some handmade jewelry. We ate a delicious dinner (I wonder if I can grow fennel in my back yard...I love fennel), complete with a scrumptious chocolate chip cake. I got to take a walk around the lake and read my book. I wasn't upset by Mother's Day talks. I talked to my mom. The only wrinkle: my Mother's Day present to myself hasn't yet arrived from Amazon.

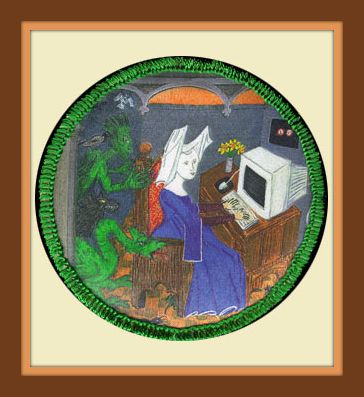

I also wanted to spend some time writing today. Earlier this year, I had such big plans. I was all set with reading for African American History month in February, and being overly optimistic, I planned some reading for Women's History month in March. Well, that didn't work out like I wanted, but I have read some interesting things since then and thought Mother's Day would be as good a time as any to write a few thoughts. I wanted to read about women's lives and experiences. I wanted to hear women's voices. Yes, such a broad objective, so that many things fit.

There were two books that were disappointing. I'll start with them since I don't have much to say about them. Things I've Been Silent About by Azar Nafisi. I listened to her do a book reading and an interview and I was interested to read her newest book about her life in Iran and her experiences with her mother and other family. The book was disjointed, the focus on her controlling mother became tiresome, and I lost interest quickly.

And Monique and the Mango Rains by Kris Halloway. This was the memoir of a Peace Corps Volunteer who spent two years in Mali working with a midwife on maternal and child health. I was interested in the topic, but the writing was flat. It didn't resonate with me nearly as much as another book about poverty and health that I read around the same time--Mountains Beyond Mountains. More on that in another post. How about a book about Abigail Adams? She's an intriguing historical figure and I was interested to learn more about her after watching (part of) the HBO series on John Adams. Portia: The World of Abigail Adams by Edith Gelles was a collection of academic essays. It felt like each could have been published as an individual paper. Gelles' intention was to write about Abigail completely on her own terms, rather than constantly linking her life and destiny to her famous husband. I thought that to be a bold claim, for so much of Abigail's life was shaped through her relationship with John. How could she be considered independently of him? But Gelles does a pretty good job looking at certain topics that have been ignored by other scholars. By analyzing Abigail's prolific correspondence, she writes about Abigail's relationship with her daughter, with her sisters, and with Thomas Jefferson. She examines the way scholarship about Abigail has changed over time. Abigail had a brilliant mind and was a prolific writer and voracious reader. Writing, for her, was a way to work through issues, to make arguments, and to conduct business with her often absent husband. She said, "There are particular times when I feel such an uneasiness...my pen in my only pleasure." Portia was a penname that she adopted and used to sign many of her letters. She identified herself with Portia, the wife of the Roman politician Brutus.

How about a book about Abigail Adams? She's an intriguing historical figure and I was interested to learn more about her after watching (part of) the HBO series on John Adams. Portia: The World of Abigail Adams by Edith Gelles was a collection of academic essays. It felt like each could have been published as an individual paper. Gelles' intention was to write about Abigail completely on her own terms, rather than constantly linking her life and destiny to her famous husband. I thought that to be a bold claim, for so much of Abigail's life was shaped through her relationship with John. How could she be considered independently of him? But Gelles does a pretty good job looking at certain topics that have been ignored by other scholars. By analyzing Abigail's prolific correspondence, she writes about Abigail's relationship with her daughter, with her sisters, and with Thomas Jefferson. She examines the way scholarship about Abigail has changed over time. Abigail had a brilliant mind and was a prolific writer and voracious reader. Writing, for her, was a way to work through issues, to make arguments, and to conduct business with her often absent husband. She said, "There are particular times when I feel such an uneasiness...my pen in my only pleasure." Portia was a penname that she adopted and used to sign many of her letters. She identified herself with Portia, the wife of the Roman politician Brutus.

I liked this bit from a letter written to her by her younger sister Elizabeth:

If ideas present themselves to my mind, it is too much like the good seed sown among thorns; they are soon crazed and swallowed up by the wants and noise of my family and children. The bad writing you must impute to my rocking the cradle.

A sentiment I can relate to.

An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination is Elizabeth McCracken's beautifully written memoir of the stillbirth of her son. She and her kind, earnest English husband are living in the countryside of France, both working on writing. She is radiantly pregnant, the adorable baby shoes have been purchased, and they have created a vision of their future life with their baby boy nicknamed Pudding. From the very beginning, McCracken lets us in on what will happen. Both her stillborn son, and the living, healthy child that will be born almost exactly a year later. But, the unraveling. Oh, the tragic and painful unraveling.

An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination is Elizabeth McCracken's beautifully written memoir of the stillbirth of her son. She and her kind, earnest English husband are living in the countryside of France, both working on writing. She is radiantly pregnant, the adorable baby shoes have been purchased, and they have created a vision of their future life with their baby boy nicknamed Pudding. From the very beginning, McCracken lets us in on what will happen. Both her stillborn son, and the living, healthy child that will be born almost exactly a year later. But, the unraveling. Oh, the tragic and painful unraveling.

Here's one section from early on:

I had just stepped over the border from happy pregnancy to grief, but I could still see that better, blither country, could smell the air over my shoulder, could remember my fluency there, the dumb jokes, the gestures, the disappointing cuisine, the rarefied climate. I knew already I could never go back, not then, not for any future pregnancy (should I be so lucky).

The sections on interacting with those who are suffering grief should be required reading for everyone. Here's a little bit.

I remember one lunch with people who had loved us in London early on, two of the most excruciating hours of my life. Nothing but that endless juggling: Other people's jobs and boyfriends. What kind of wine to order. This was two weeks after Pudding died. I might have been something like that gothic character one step short of total ruin: I wanted to rock and sing lullabies and hold out my torn, bloody nightgown and run my hands through my wild hair, and yet I knew you weren't supposed to do such things in polite society. My hair was uncombed, and my face was puffy from lack of sleep and crying and too much wine, and my clothes were what I'd salvaged from the middle of my pregnancy, because of course even though people might pretend nothing was out of the ordinary I had the body of a woman two weeks postpartum, soft and wide around the middle, and if I'd been one step worse off I might have lifted up my shirt to display my still livid stretch marks.

But, I didn't. I could feel how uncomfortable my mere presence made people feel, and I couldn't bear it. So, I sat in this Indian restaurant and listened. Sometimes, a piece of palaver came loose and shot straight toward me and somehow I caught it and tossed it back.

All the while, all I could think was: Dead baby dead baby dead baby.

And finally, All God's Critters Got a Place in the Choir by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and Emma Lour Thayne. This is a book of essays about being female and Mormon, about friendship, sisterhood, and community, about motherhood and writing. Like any collection of essays, there were some that were more personally meaningful to me, but this is such a great compilation of their writing. Like Abigail Adams, they both describe their absolute need to write. Emma Lou Thayne is a poet and author and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich is a historian. But, this book contains their personal lives, bubbling over with the richness of their lives and their thoughtful insights.

And finally, All God's Critters Got a Place in the Choir by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and Emma Lour Thayne. This is a book of essays about being female and Mormon, about friendship, sisterhood, and community, about motherhood and writing. Like any collection of essays, there were some that were more personally meaningful to me, but this is such a great compilation of their writing. Like Abigail Adams, they both describe their absolute need to write. Emma Lou Thayne is a poet and author and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich is a historian. But, this book contains their personal lives, bubbling over with the richness of their lives and their thoughtful insights.

Early on, Ulrich talks about gifts and talents. "I have come to believe that talent is a inner drive that propels a person to take time." The title of the book comes from a song:

All God's critters got a place in the choir--

Some sing low; some sing higher,

Some sing out loud on the telephone wire,

And some just clap their hands,

Or paws

Or anything they got.

It brings to mind a group of people, all working together for a common objective, but each utilizing their own unique gifts and abilities. The first few chapters filled me with such optimism about using my own talents in a way that both helps me grow them, and contributes to some larger good.

The essays that make up the bulk of the book are filled with experiences from their lives--dealing with cranky neighbors, watching a mother die, going visiting teaching, raising children, and connecting with women across the globe.

In its totality, their book celebrates women's gifts, not as anything generically applied to all with XX chromosomes, but each individual woman's gifts and contributions, unique and precious. For example, Ulrich describes herself this way: "As a daughter of God, I claim the right to all my gifts. I am a mother, an intellectual, a skeptic, a believer, a crafter of cookies and words." Her own identity as a daughter of God, different from any other.

Sunday, May 10, 2009

Women's Voices

Labels:

Off the Stacks

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment